No Country for Old Men

There’s no telling what may generate an idea for a BLOG essay. It can be spurred by some everyday occurrence that, for unexplainable reasons, triggers a flurry of words to jump from fingers to keyboard. It can awaken a troubled sleeper in the night forcing unsteady hands to jot down reminder notes for development on the morrow. It can leap off the pages of a compelling novel or poem, or explode off the screen of a gripping motion picture or provocative TV drama, setting one onto introspective paths. Sometimes essays emerge out of the drama of athletic competition, or military combat, where the difference between victory or defeat, glory or shame is both subtle and nuanced. And since politics defines and directs so much of our social intercourse, it never ceases to ar0use opinions and passions that beckon us to think out loud, where our aggravations and confoundments find voice.

So it is that the a book and movie title has gripped me over the past six months, teasing me with the thought that an essay just might be in the offing. But the generation of such an essay has neither been easy to conceive nor compose. Yet I couldn’t shake the title, No Country for Old Men, for it seemed to speak volumes about what was playing out in American political theater. Neither Cormac McCarthy, the novelist, nor the Coen brothers in their film adaptation would likely connect their title to what I am now writing. The truth is I never read the book or saw the movie. Critical reviews of both led me to conclude that I had no appetite for sampling such a meal of nihilistic violence. Yet the title grabbed me, nonetheless, large owing to its all-too-obvious, art-mimicking-life resonance with current events..

I doubt there is a more concise and apt commentary on the melodrama of our American political process, featuring two really old men preparing to joust once again in the electoral arena that seems to have scared off most, if not all would be challengers. What keeps Ms. Haley going is a mystery to me and most political analysts. Perhaps it is sheer grit or maybe her intuition from having fought and won a few of her own electoral battles, that one or both of these combatants will be unable to answer the bell when ballots signal the start of this fall’s election match. Yet as it stands today, this year’s presidential election looks much like a rerun of the 2020 geriatric contest that, so pollsters tell us, most Americans don’t care to repeat.

Before I go further, I think it good that I lay down two cards on the expository table lest readers jump to unwarranted conclusions about agendas they may think are lurking behind what I’m about to say.

The first card? I am no ageist. In fact, the company of people I most treasure are those whose life experiences make it easy for them to recognize and appreciate literary and cultural allusions from those dark ages of history before century numbers hit 2000. I came to that conclusion years ago while teaching young people in middle and high school. Their lack of knowledge of, or even interest in life before they were born reduced my most clever classroom asides, jokes and puns to irrelevant, unintelligible gibberish. Even my nightly dose of Jeopardy, with its preferred curriculum of recent pop culture trivia at the exclusion of so much from history’s great catalogue of dates, names and places, leaves me shaking my head. Oh where have you gone Art Fleming? Clearly I am, whether measured in years or attitudes, someone for whom the phrase, Old Man, holds special applicability and relevance.

And the second card? I don’t consider myself an adherent of or devotee to any political party. In fact, my voting selections since 1972, when I cast my first ballot, have included McGovern, Ford, Anderson, Reagan, 2 in the Bush clan, Clinton, McCain, Kerry, Trump and Kasich, who, like Anderson, were essentially write-ins, so great was my rejection of what the two dominant parties had to offer. So the comments that follow bear no partisan affinity for or commitment to whomever the political herds of elephants and donkeys settle on nominating.

So with nothing up my sleeve other than a penchant for stating the obvious, I offer my reaction to the deja vu of the political landscape in which we now find ourselves. My great hope is that America is really not a country of or for old men, even if our government clearly suggests otherwise. The map below brings this reality into focus:

Mathematical medians are not averages, but midway points, in this case separating the younger half of our population from the older half in equal measure. By listing median ages for each state, the Census Bureau is letting us know that there are as many of us under 38.8 years of age as there are of us above that number. By this reckoning some states, like Utah and North Dakota have a younger cast right now while Maine and Florida seem to attract, or hold onto, more older folks. That half of America on the high side of the ledger, those who are 75 and up, who have earned the right to be respectfully called seniors and elders or pejoratively referred to as “long in the tooth”: they represent 6.9% of our entire population. If we factor out the more than 70 million Americans under the voting age of 18, then the median age of eligible voters would be much higher, perhaps in the low 50s, but still significantly younger than the old men now leading in the polls.

Both Mr. Biden, born in 1942, and Mr. Trump, born in 1946, fall within our oldest demographic stratum. That makes them 44 and 40 years older, respectively, than half of the American population, and quite unlike those 25-29 year olds—the millennial or Gen Z-ers,—who are now our single largest adult group. Or to put it another way, both Mr. Biden and Mr. Trump are four decades removed from when they celebrated their 38th birthdays, having passed America’s current median age back in the early 1980s, when our country was much different than it is now. Remember those good old days?

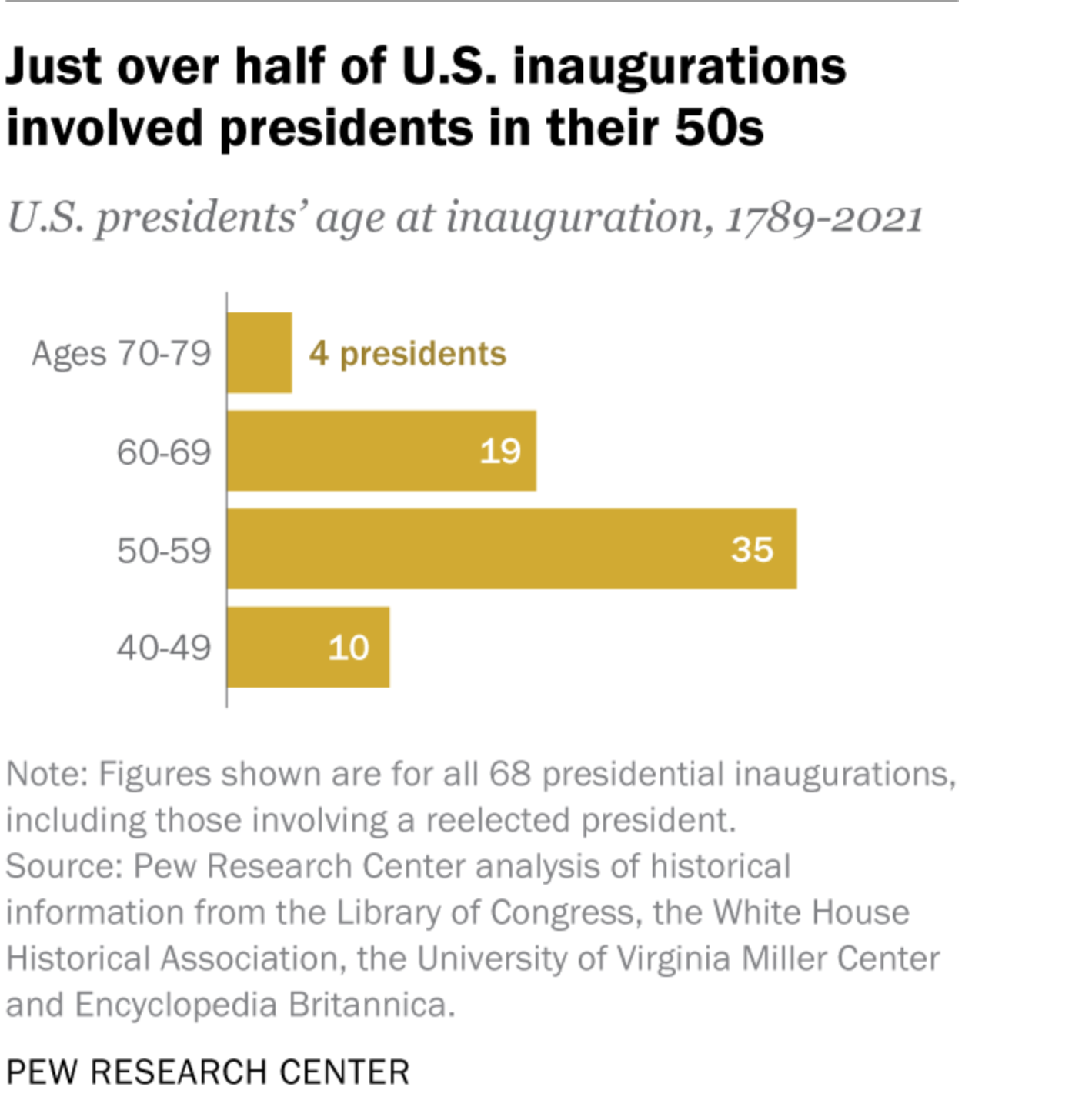

Science, medical technology, and healthier diets and lifestyles have certainly pushed human longevity much further than when these two presidential aspirants were in their prime. Now I must admit that both Biden and Trump still look reasonably healthy, as well they should given the amount of daily rest they get and the support they count on from their trainers, handlers, and make-up specialists. Even so, the sight of shuffling steps and hanging jowls, and the embarrassment of frequent lapses of verbal recall and the oft-documented wanderings of thought suggest they are now closer to senility than they are to their former vitality. The question needs to be asked, not as an asterisk attached to their resumes but as a measure of their qualifications to handle our nation’s most important and most stressful of jobs: are these two old men the best we have, he best we can find to lead us? A quick review of the American presidency shows us that the median age of our chief executives since 1789 has been much younger (55 years to be exact) than either of them currently is. In fact, they are now between 23-27 years past that historic presidential median.

Only Dwight Eisenhower, who left office after just turning 70 and having suffered both a heart attack and a stroke while in office, and Ronald Reagan who reached 77—shaky memory and all—come close to Trump and Biden, both of whom would be trying to effectively lead the country as men in their early to middle 80s. To put this in perspective, Americans aged 80-84 represent 1.8% of our entire population, underscoring how much our leadership, should either of them be reelected, will resemble more of a gerontocracy than what our founders likely ever imagined when they set 35 as the minimum age for our highest elected office.

With no mandated age limits, a sizable portion of our governance at the national level is now in the hands of more older men and older women than we’ve seen in over a century. In fact, our current Senate is the 2nd oldest in our history, while the House ranks 3rd oldest. And the elderly trend in our two legislative bodies seems to be increasing, not decreasing. The 118th Congress now in session includes 100 senators who are 12 years older on average than were their predecessors in the 1980s. Our 435 representatives are, on average, older by 9 years than the lower house was in that same decade. While age may ensure a level of experience and wisdom among our leaders, it also brings with it a degree of inflexibility and dogmatism that often accompanies extreme longevity in office. Certainly the dysfunctions of the current Congress in being unable to agree on budgets, or successfully manage impeachments, or resolve our immigration crisis or fund our allies engaged in war bear witness to an intransigence among the personalities we’ve elected to represent us. Age not only stiffens our joints—it has a way of hardening our attitudes and petrifying our convictions too, neither serving the best interests of a legislative body that thrives or fails on its ability to compromise.

Ironically, the Supreme Court, so often viewed as the haven of graybeards, is the youngest of our three branches of government. These guardians of our Constitution have, since 1789, welcomed justices as young as 32 and as old as 90. The median age for the current group of nine judges, all appointees for life, is 62, with liberal and conservative leanings found on both the older and younger halves of that spectrum.

A telling contrast to our elected leaders can be found among those to whom we entrust our very lives and in whose hands we place the security of our nation: the members of our armed forces. They too are government employees. Ironically they are held to very strict requirements concerning how old they can, and can’t be, in effectively serving their country. This even applies to those at the very highest positions of authority and power, our generals and admirals. “Mandatory retirement age for general and flag officers is age 64. Officers in O9 and O10 positions may have retirement deferred until age 66 or…until age 68 by the President.”* What does it say about us when the expectations of vitality and competency we place on our warriors in the field are far more demanding than they are for the commander in chief under whom they serve and receive their orders?

Given the geriatric reality of our current national government, one can’t be faulted for asking why: why have we as an electorate permitted or settled for such a state of aged leadership? Is it that we have been so busy taking care of our own survival needs that we’ve become a bit lazy in exercising our democratic responsibilities? I don’t think Americans historically or naturally have favored the very old over those in the prime of their lives. That has more typically been found in Asian countries whose traditions extend to elders a respect and reverence that is much rarer in the West. In contrast, we Americans have been and continue to be much more infatuated with youthful energy and creativity, along with demonstrable strength of mind, body and spirit. How else do we explain the prioritization of time and money we now give to entertainment, physical fitness, and cradle-to-grave athletic competition above all else? Yet when it comes to those whom we choose to craft our laws, articulate our shared values, moderate our differences and represent us in the community of nations—we seem to prefer people who not only are well past their prime. They often can’t remember when that was, at least not in accurate recollection.

Why is it, then, that we now seem less amenable to electing men and women in their 40s, 50s, or 60s than we were in the past? I’m sure we have many who are more than capable of leading us, even in times as foreboding and complex as we now face. But something has changed … changed in us who cast the votes, attend the rallies, and send our monies to fund the campaigns of our champions.

Could it be that many of us become so unmoored by social and cultural change that we seek refuge in the promises of elders boasting of their imagined prowess as they promise to restore our nation to its former greatness? Or is it that many of us have become so ignorant of and disconnected from our past—its triumphs and it failings—that we turn a blind eye to what was once taken for granted or valued as common sense? Perhaps we have allowed ourselves to become so polarized in our judgments about what America is, was and should be that we no longer have the will to constructively dialogue with our ideological opponents in order to find common ground? Or maybe, just maybe, we have become so insecure in our values, so entrenched in our dogmatisms that we find greater comfort clenching fists and locking arms in winner-take-all battles against "them” than in courageously opening our hands and minds to honestly engage “us” in the give-and-take of negotiated compromise from which America’s pluribus has achieved its greatest moments of unum.

In my judgement this is no country for old men because it never has been. And, in particular, it is no time for these two old men now who vie for our affection, our allegiance, our money and our votes. Neither of them, regardless of what their handlers say to the contrary, is close to bringing his A-game to the incredibly complex and history-transforming issues our country now faces inside, outside and on our borders. Perhaps Joe Biden and Donald Trump might have been up to it 20 or 30 years ago, but that day has passed. For they have now become what all of us become when we survive into our 8th and 9th decades: more of what we’ve always been.

Story telling, truth-bending, name-dropping, glad-handing Joe Biden is not different than he used to be—he’s more of what he’s always been. Self-promoting, bullying, name-calling and history fabricating Donald Trump isn’t different than he used to be—he’s more of what he’s always been. Personalities don’t change over time as much as they become more fossilized and exaggerated. And isn’t that what we are seeing and hearing all the time? In interviews, press conferences and at party rallies; in prepped sound-bytes and moments of off-the-cuff banter and spur-of-the-moment tweats: a day doesn’t go by that we aren’t reminded of so many of those traits and mannerisms that we recognize in our elders who are in decline. They can be cranky and crude; impatient and irritable towards those who challenge or disappoint them. The recall or inappropriate use of names, details and events regularly betray their muddled state of mind. And that senior tendency to retell their stories about what they once did, said, or promised are invariably filled with inaccuracies, revisions and aggrandizements. So the question for me, and the question for all of us who will, or should, have a say in who becomes our next president is this: how dare we entrust the future of our country to these two old men?

As I write this, awaiting a decision by the high court about Mr. Trump’s regrettable and inexcusable conduct upon leaving office, I do so hoping that, barring some “act of God” as insurers might put it, we as Americans will put our money and our votes where our clearest thoughts and best reasoning are making so very clear. For our country deserves better than the presidential choices now lining up to duke it out again this fall. There is a reason that men and women my age choose to retire or are, as our military confirms, forced to let step aside to let others, younger and now more capable, carry on in their place. It is my hope and prayer that we, as a nation, may be spared the disappointments and damages that are certain to come should we elect either of these once notable, but now mostly just old, men.

——————————

*Federal Law 10 U.S. Code section 1253, O9 and O10 are the top Navy and Army/Air Force ranks which we more commonly call Admirals and Generals.