Eat, drink, and…

Does the juxtaposition of these two images revile you or bring some revelation to light? Both have long and checkered histories, and both continue to inspire indulgence as well as introspection. Each in its own way symbolizes hope, and each portrays danger, sadness and death. Taken together they seem not to fit at all. In fact one cheapens and profanes the other when viewed side-by-side. But for me they trigger thoughts about a distinctly human quality that so defines who we are—our ability to remember, and to forget.

On both tables can be found the products of the harvest. Those distilled and sold for consumption by anyone of age or with inclination and opportunity to imbibe have one very clear purpose—pleasure. Alcohol can be pleasing to the taste and warming to the spirit, physiologically, psychologically, and socially. In satisfying us on so many levels, it rarely disappoints. Beers of every flavor and hue, wines from dry to sweet, and liquor to be enjoyed in mixed concoctions, on the rocks or straight from the bottle—they are ours for the taking whether we’re wealthy or indigent. And they are made all the more enticing in their many colors and imaginative decanters, appealing to our deepest yearnings for social identity and sexual desirability.

More than just a tasty or refreshing beverage, alcohol has become an emblem of adulthood in 21st Century America, granting us permission to indulge, to do what makes us feel older, rebellious or more sophisticated. It offers us the opportunity to suspend our inhibitions, to act crazy, get wild and free ourselves from suffocating obligations and the cares that so heavily weigh upon us. Drinking to intoxication—which seems both means and ends for the 25% of us who do it with regularity—grants us passport to a state where we can relinquish self-control, act the juvenile once again, and trust ourselves to the care of others. To these special or unlucky souls upon whom the responsibility of looking out for us falls, getting us safely home, cleaning up our mess, and otherwise explaining and excusing our behavior thrusts them into a parental role that few really want and none deserve.

Euphemistically we often refer to our bottled elixirs as “adult” beverages, and when we raise our glasses in our favorite watering holes, parties or stadium parking lots we affirm a very old existential bond with those whom we join in our consumption:

“Cheers!” “To your health” “To the good life” “Eat, drink and be merry.”

This last toast occasionally adds the troubling clause, “for tomorrow we die,” which too often has become a self-fulfilled prophecy when lives abruptly end in poisoning, balcony diving or vehicular tragedy. And inasmuch as alcohol can get the best of any of us, impairing our reflexes, blurring our judgment, and altering our ability to be in charge of our actions or decisions, it is far less a tonic than an anesthetic. It is, for too many in our country, the pain-killing drug of choice.

Two tables are pictured at the top of this essay. One set for a weekend bash, where at least one guest will have to be driven home. The other is more austere: a solitary glass balancing a half-torn morsel of bread on a white tablecloth. Christians recognize these as the essential elements of their faith. Next to the cross they capture what it means to be a follower of Jesus. Whether ingested sacramentally or emblematically, together they symbolize that relationship with God that joins each believer to that unique person in whom they believe the Deity most truly and powerfully spoke. Whenever Christians gather around tables set with bread and wine, as they will on Thursday of this culminating week of Lent, they do so seeking to traverse time and place in joining him in Jerusalem on the eve of his death.

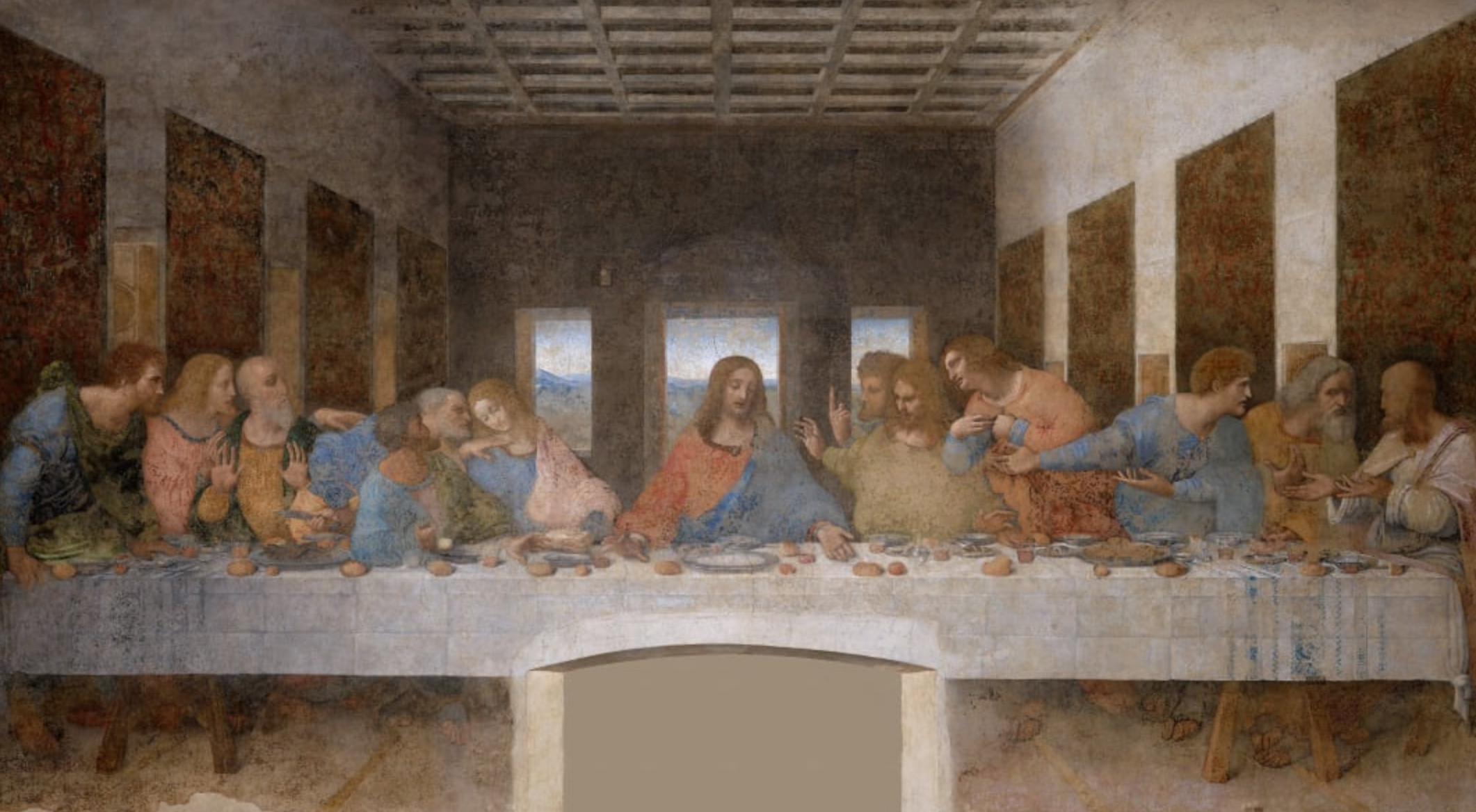

The Church commemorates this as Maundy Thursday, the occasion of the Last Supper, so familiar in its 15th Century rendering by Leonardo DaVinci:

or hauntingly surreal in Salvadore Dali’s 20th Century conception:

It was on this night that Luke and Paul* recall Jesus issuing two specific commands, in Latin mandatum, from which Maundy Thursday takes its name: Love one another and remember. Of these two, the latter jumps out at me in its dissonance from the gospel of our own age. For while Jesus implores us to “eat, drink and remember,” we are encouraged, sometimes even pressured, to “eat, drink and forget.”

Can two commands be more conflicting? Can the images they invoke, of eucharistic (“thanksgiving” in biblical Greek) fellowship or “party hardy” revelry say more about our values, our priorities or our faith? If put into liturgical dress, they each promise what they, in fact, have the power to deliver…

The cup of booze that we drink to excess, is it not an invitation to forget…

the frustrations of work and home,

the angst of our despair and hopelessness,

the helplessness of being unable to fix our many problems,

the realization of our loneliness and inevitable mortality.

The cup of blessing that we drink, is it not an invitation to remember…

who we are as children of a loving God,

who we are as sinful and fallible human beings,

who we are as redeemable and forgiven men and women,

to whom we belong, in eternal fellowship, as brothers and sisters in Christ.

We march to the drumbeat of another Lenten season, bringing us, at last, to destinations whose archaic signposts read Gethsemane and Golgotha. Dinner invitations have been sent out, but only a handful will make it to that secret upstairs room. One will exit early in betrayer’s haste, another will plead amnesia when exposed, and the rest will hide out until the coast is clear. And those who relive these moments on this Maundy Thursday will do so because of those who preceded them in obeying the rabbi’s command on that fateful night so long ago. They ate, drank, and remembered. Time and testimony will confirm whether we do too, or whether we just forget.

*Paul’s letter to the Christians in Corinth (I Cor 11:23-26) likely preserves the earliest written recollection of Jesus' command, which appears in similar construction in Luke 22:19, composed sometime later in the first century. (The full text is reproduced at the bottom of the Twilight Reflections webpage for this week.)