Mad About Basketball

Hands on my keyboard, eyes darting from laptop to television screen, I try to stay composed while composing this week’s essay. It isn’t easy. Over the years I’ve become more at home multi-tasking, with music or TV images competing for my attention, fingers playing their tune on Mac, my keyboard of choice. If it sounds a bit mad to you, I can live with that. After all it is March, and this episode of madness is a particularly addictive form of American entertainment.

If you have watched any, or most of the 63 NCAA winner-take-all men’s basketball games, including the conference championships that preceded them, you know why madness is such an apt descriptor for what is happening to us. We are madly passionate about our teams, not in any sense of rage—except when referees get it wrong--but in the exuberance of school spirit and love of athletic competition. Should we expect anything less from ourselves when our favorite term of endearment is fan-atic? Really? Aren’t fanatics people who are a bit off, crazy in fact, lacking common sense, self control or both? I don’t know anyone who would want to be so identified. Yet when it comes to this particular tournament, fanaticism and crazy are sometimes hard to distinguish, especially when you consider what big-time sports now mean to us, individually and collectively, in our country.

March Madness—and its autumn gridiron twin—have reshaped many of our values and aspirations. And I say this as one who is quite caught up with “the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat” that so captivates us over three successive weekends each spring. But the longer I have watched this high point of American collegiate sport, I am concerned and disappointed in what it says about us as a people at this point in our nation’s history.

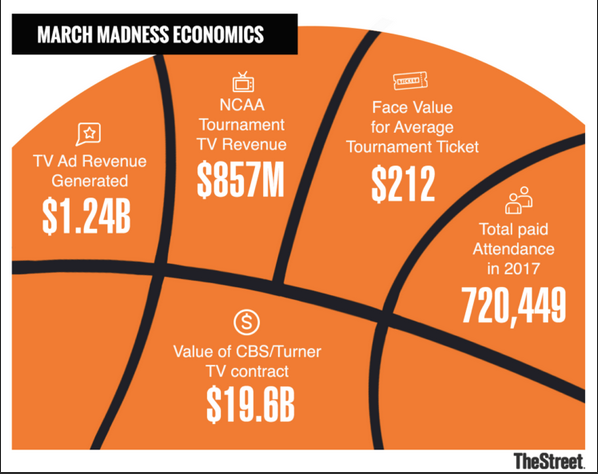

Three things in particular trouble me as I watch, root for my favorites, and brood over their disappointments. The first has to do with the role and place of big time sports on America’s college and university campuses. Where once our institutions of higher education regarded sports as part of the social vibrancy of campus life, offering students a healthy diversion from the rigors of academia, they now are the tail wagging a very large NCAA dog—dictating so many of its priorities and policies that affect facilities, schedules, admissions and scholarships, and finances. And why not? The top 48 college football programs bring in between $14-$104 million to their school’s respective budgets, while first-rank men’s basketball teams add $2-$17 million. Bowl games and national tournaments provide thick icing to this rich interscholastic cake, whose many layers consist of ingredients supplied by generous alums and boosters, television networks, and gate receipts.

And that was five years ago!

Ironically, only 25 of the nation’s 1,100 NCAA college and university athletic departments operate in the black. Sports programs with huge stadiums, arenas and natatoriums, large coaching staffs, scouts, trainers, counselors and academic support resources and tons of equipment cost quite a bundle. Nonetheless, the income generated by big-time collegiate football and basketball programs is large enough to float the other sports that draw so many women and men to our campuses. One might question why schools put so many of their financial eggs in their athletic baskets. Well there is tradition, which for some institutions goes back into the 1800s. And there is alumni pride, good will and a network of $upport that helps us understand the salary priorities illustrated below. Considering how many other occupations are more critical to our happiness, well being and survival, this really is madness!

My second concern is the impact that big time sports now has on those whose involvement and investment in it is both personal and total: the athletes and their families. There was a time, not that long ago, when sports was considered a positive outlet for youthful energies and talents. In fact, the more sports you could interest your child in pursuing, the better. The three-sport participant, which is now becoming a rarity in middle and high schools, was an ideal of athleticism and a staple for interscholastic and intercollegiate teams. But with the dream of college scholarships, the allure of multi-million dollar professional contracts, and the mythicized mantra that you can be whatever you dream—athletic specialization has reshaped the recreation and fun of sports for many of our kids. Between private coaches, camps—many of them a pipeline to collegiate and professional teams—young people are targeted, groomed, trained and cultivated to become some school’s top recruit and some franchise’s top draft pick. Now that may sound a bit sinister or Orwellian in design. The fact remains, when it comes to sports in America, many are called but few are chosen as this chart makes clear.

Those who beat these long odds and make it into the collegiate ranks quickly realize that it isn’t quite what they expected. The promise of being a student-athlete quickly gives way to the realization that their coaches and programs own most of their time, in and out of season. While their school is profiting in many ways from their commitment of time and talent, theirs is the life of an indentured servant, a relationship that injury, being cut from the team, or graduation (for those who do graduate) will bring to an end. Only a few, a very few, will be able to continue playing and competing in the professional leagues which so inspired their youthful dreams.

Athletes aren’t the only ones getting used when universities become cogs in the machine of our multi-billion dollars sports enterprise. The integrity of the schools is called into question whenever they add athletes to their teams whose intention is to jump to the NBA after getting their desired exposure in the NCAA tournament. Much the same happens when they accept those who transfer for a year or two, positioning them on a team more likely to improve their chances for professional notice. Only half of this year’s Sweet Sixteen teams featured rosters with more upperclassmen than freshmen or sophomores, and many had late career transferees to bolster their, and their team’s chances at winning. Two of this year’s likely finalists, Duke and North Carolina, are dominated by underclassmen, many of whom will turn pro without graduating. The degree to which our colleges have bought into this symbiotic relationship between players, agents, and professional teams is seen in how few of them observe those standards of inclusion and diversity that govern admission and hiring throughout the university system. Everywhere, that is, but in sports, where athletic merit alone determines who dons the uniform and gets his or her opportunity to compete.

The last of my concerns rests with the moral vacuity which big-time sports helps foster in our society, affecting the very fabric of our character. It wasn’t that long ago when gambling was recognized as a crippling flaw that exploited the weakness of those who fell under its spell while often diminishing the lives and livelihoods of those who became its victims. Today it is promoted round the clock as both a desirable pastime and a normal, acceptable way for men and women to vicariously enjoy the thrill of sport. Fantasy leagues have become a year-round obsession, generating a level of passion and financial commitment that many find better than the real thing. What amazes me is that, even in this bizarre era of COVID-fueled subsidies and rising inflation, so many are willing to risk what they have for the chance to strike it rich betting on sports. If that isn’t madness, I don’t know what is.

Even the Mannings seem to have some reservations about what this may be doing to our country. While shilling for Caesars, they offer a “know when to say when” warning that is reminiscent of the public service disclaimers with which beer companies sometimes temper their party hardy gospel. But whether we’re talking about gambling, chronic intoxication, fans celebrating a win by destroying property—the appearance and meaning are hard to ignore: this is Mad. It would all be quite laughable if it weren’t so true. But to the degree that we have allowed our ambitions and our acquisitiveness (sounds better than greed, doesn’t it) to cloud our perspective, perhaps the madness of each March is a good thing. For in its excitement and its excesses it shows us who we are when at our very best, and who we can become when caught up in the madness of the moment, even those that recur every March.